Request Radio Tv Coverage Of The Trial Of In The Sandiganbayan

This document was uploaded by user and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this DMCA report form. Report DMCA

Overview

Download & View Request Radio Tv Coverage Of The Trial Of In The Sandiganbayan as PDF for free.

More details

- Words: 700

- Pages: 1

Loading documents preview...

Re: Request Radio-Tv Coverage Of The Trial Of In The Sandiganbayan Of The Plunder Cases Against The Former President Joseph E. Estrada. A.M. No. 01-4-03-S.C., June 29, 2001 Facts: The travails of a deposed President continue. The Sandiganbayan reels to start hearing the criminal charges against Mr. Joseph E. Estrada. Media seeks to cover the event via live television and live radio broadcast and endeavors this Court to allow it that kind of access to the proceedings. Public interest, the petition further averred, should be evident bearing in mind the right of the public to vital information affecting the nation. In effect, the petition seeks a re-examination of the 23rd October 1991 resolution of this Court in a case for libel filed by then President Corazon C. Aquino: “xxx "Representatives of the press have no special standing to apply for a writ of mandate to compel a court to permit them to attend a trial, since within the courtroom, a reporter's constitutional rights are no greater than those of any other member of the public. Massive intrusion of representatives of the news media into the trial itself can so alter or destroy the constitutionally necessary judicial atmosphere and decorum that the requirements of impartiality imposed by due process of law are denied the defendant and a defendant in a criminal proceeding should not be forced to run a gauntlet of reporters and photographers each time he enters or leaves the courtroom. xxx” Issue: Whether the press should be allowed to air Estrada’s trial to the public. Held: Admittedly, the press is a mighty catalyst in awakening public consciousness, and it has become an important instrument in the quest for truth. Recent history exemplifies media's invigorating presence, and its contribution to society is quite impressive. The Court, just recently, has taken judicial notice of the enormous effect of media in stirring public sentience during the impeachment trial, a partly judicial and partly political exercise, indeed the most-watched program in the boob-tubes during those times, that would soon culminate in EDSA II. The propriety of granting or denying the instant petition involve the weighing out of the constitutional guarantees of freedom of the press and the right to public information, on the one hand, and the fundamental rights of the accused, on the other hand, along with the constitutional power of a court to control its proceedings in ensuring a fair and impartial trial. When these rights race against one another, jurisprudence7 tells us that the right of the accused must be preferred to win. An accused has a right to a public trial but it is a right that belongs to him, more than anyone else, where his life or liberty can be held critically in balance. A public trial aims to ensure that he is fairly dealt with and would not be unjustly condemned and that his rights are not compromised in secrete conclaves of long ago. A public trial is not synonymous with publicized trial; it only implies that the court doors must be open to those who wish to come, sit in the available seats, conduct themselves with decorum and observe the trial process. In the constitutional sense, a courtroom should have enough facilities for a reasonable number of the public to observe the proceedings, not too small as to render the openness negligible and not too large as to distract the trial participants from their proper functions, who shall then be totally free to report what they have observed during the proceedings. The courts recognize the constitutionally embodied freedom of the press and the right to public information. It also approves of media's exalted power to provide the most accurate and comprehensive means of conveying the proceedings to the public and in acquainting the public with the judicial process in action; nevertheless, within the courthouse, the overriding consideration is still the paramount right of the accused to due process which must never be allowed to suffer diminution in its constitutional proportions. Unlike other government offices, courts do not express the popular will of the people in any sense which, instead, are tasked to only adjudicate justiciable controversies on the basis of what alone is submitted before them.

Related Documents

233126853 Re Request For Live Radio Tv Coverage 2

January 2021 0

The Trial In The Merchant Of Venice

February 2021 0

Radio-tv Experimenter N569_1960

March 2021 0

In The Paradise Of The Sufis

February 2021 1

The Importance Of The Arts In Education

March 2021 0More Documents from "Jesse Cook-Huffman"

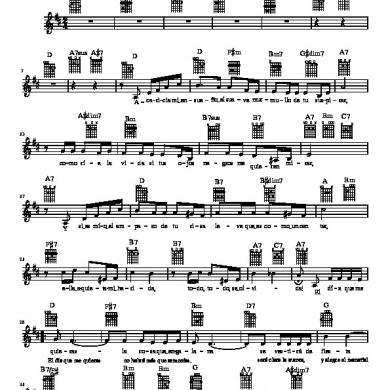

Bless Them O Lord (wedding Song)-1.pdf

January 2021 0

Quimica General (luis Escobar)

February 2021 1

Lamaran 1

January 2021 1

Psvare - Ra [compatibility Mode].pdf

February 2021 1