Right To Be Forgotten Cyber Law

This document was uploaded by user and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this DMCA report form. Report DMCA

Overview

Download & View Right To Be Forgotten Cyber Law as PDF for free.

More details

- Words: 4,696

- Pages: 19

Loading documents preview...

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

CYBER LAW PROJECT “RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN” PROJECT SUBMITTED TO: MRS. DEBMITA MONDAL (ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF CYBER LAW)

PROJECT SUBMITTED BY: RAHUL MANDAVI Semester VII, Section A

ROLL NO. 125 SUBMITTED ON: 26.09.2016

HIDAYATULLAH NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Contents Declaration .............................................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ iii Aims and Objectives .............................................................................................................................. iv Research Methodology ........................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 What is Right to be Forgotten ................................................................................................................. 2 The European Union Perspective and the United States Perspective ..................................................... 6 Criticism.................................................................................................................................................. 8 CONCLUSIONS................................................................................................................................... 12 WEBLIOGRAPHY............................................................................................................................... 13

i

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Declaration

I hereby declare that this research work titled “RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN” is my own work and represents my own ideas, and where others’ ideas or words have been included, I have adequately cited and referenced the original sources. I also declare that I have adhered to all principles of academic honesty and integrity and have not misrepresented or fabricated or falsified any idea/data/fact/source in my submission.

(RAHUL MANDAVI)

ii

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Acknowledgements

I, Rahul Mandavi, would like to humbly present this project to MRS. DEBMITA MONDAL. I would first of all like to express my most sincere gratitude to MRS. DEBMITA MONDAL for her encouragement and guidance regarding several aspects of this project. I am thankful for being given the opportunity of doing a project on ‘RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN’. I am thankful to the library staff as well as the IT lab staff for all the conveniences they have provided me with, which have played a major role in the completion of this paper. I would like to thank God for keeping me in good health and senses to complete this project. Last but definitely not the least, I am thankful to my seniors for all their support, tips and valuable advice whenever needed. I present this project with a humble heart.

- RAHUL MANDAVI SEMESTER VII, SECTION A, ROLL NUMBER 125 BA.LLB (HONS.)

iii

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Aims and Objectives

I.

To understand what is Right to be Forgotten.

II.

To understand the EU perspective and US perspective

III.

To understand the Criticism of right to be forgotten .

iv

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Research Methodology

Nature of Research This research work is descriptive in nature. It describes the perspective of Right to be Forgotten.

Sources of Data This study is done with the help of secondary data. This secondary information has been obtained from published sources such as books, journals, websites, newspapers, research works etc.

v

INTRODUCTION

Mario Costeja González spent five years fighting to have 18 words delisted from Google search results on his name. When the Spaniard googled himself in 2009, two prominent results appeared: homeforeclosure notices from 1998, when he was in temporary financial trouble. The notices had been published in Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia and recently digitised. But their original purpose – attracting buyers to auction – had lapsed a decade ago, as had the debt. Costeja González asked the newspaper to remove them. When that was unsuccessful, he challenged Google, and the case was eventually elevated to the European Court of Justice, Europe’s highest court. Forgetting and remembering are complex, messy, human processes. Our minds reconstruct, layer, contextualise and sediment. The worldwide web is different. As Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page described in their original Stanford research paper, the web is “a vast collection of completely uncontrolled heterogeneous documents”. And search engines take that corpus and give it perpetual, decontextualised freshness. Vast catalogues of human sentiments and stories get served up at the mercurial whims of black box algorithms – algorithms that Brin and Page initially described as “inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers”, in a way that is “difficult even for experts to evaluate” and therefore is “particularly insidious”. The crude, timeless nature of digital memory – and the unquestioned power of private, commercially motivated companies that control it – was a challenge that 59-year-old Costeja González decided to tackle directly.1

1

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/feb/18/the-right-be-forgotten-google-search

1

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

What is Right to be Forgotten

The right to be forgotten is a concept discussed and put into practice in the European Union (EU) and Argentina since 2006. The issue has arisen from desires of individuals to "determine the development of their life in an autonomous way, without being perpetually or periodically stigmatized as a consequence of a specific action performed in the past." There has been controversy about the practicality of establishing a right to be forgotten to the status of an international human right in respect to access to information, due in part to the vagueness of current rulings attempting to implement such a right. There are concerns about its impact on the right to freedom of expression, its interaction with the right to privacy, and whether creating a right to be forgotten would decrease the quality of the Internet through censorship and a rewriting of history, and opposing concerns about problems such as revenge porn sites appearing in search engine listings for a person's name, or references to petty crimes committed many years ago indefinitely remaining an unduly prominent part of a person's Internet footprint.

Conception and proposal Europe’s data protection laws are intended to secure potentially damaging, private information about individuals. The notion of "the right to be forgotten" is derived from numerous pre-existing European ideals. There is a longstanding belief in the United Kingdom, specifically under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act, that after a certain period of time, many criminal convictions are “spent”, meaning that information regarding said person should not be regarded when obtaining insurance or seeking employment. Similarly, France values this right - le droit d’oubli (the right to be forgotten). It was officially recognized in French Law in 2010. Views on the right to be forgotten differ greatly between America and EU countries. In America, transparency, the right of free speech according to the First Amendment, and the right to know have typically been favoured over the obliteration of truthfully published information regarding individuals and corporations. The term "right to be forgotten" is a relatively new idea, though on May 13, 2014 the European Court of Justice 2

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN legally solidified that the "right to be forgotten” is a human right when they ruled against Google in the Costeja case. In 1995 the European Union adopted the European Data Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC) to regulate the processing of personal data. This is now considered a component of human rights law. The new European Proposal for General Data Protection Regulation provides protection and exemption for companies listed as "media" companies, like newspapers and other journalistic work. However, Google purposely opted out of being classified as a "media" company and so is not protected. Judges in the European Union ruled that because the international corporation, Google, is a collector and processor of data it should be classified as a "data controller" under the meaning of the EU data protection directive. These "data controllers" are required under EU law to remove data that is "inadequate, irrelevant, or no longer relevant", making this directive of global importance.

Current legal frameworks The right to be forgotten "reflects the claim of an individual to have certain data deleted so that third persons can no longer trace them." It has been defined as "the right to silence on past events in life that are no longer occurring." The right to be forgotten leads to allowing individuals to have information, videos or photographs about themselves deleted from certain internet records so that they cannot be found by search engines. As of 2014 there are few protections against the harm that incidents such as revenge porn sharing, or pictures uploaded due to poor judgement, can do. The right to be forgotten is distinct from the right to privacy, due to the distinction that the right to privacy constitutes information that is not publicly known, whereas the right to be forgotten involves removing information that was publicly known at a certain time and not allowing third parties to access the information. Limitations of application in a jurisdiction include the inability to require removal of information held by companies outside the jurisdiction. There is no global framework to allow individuals control over their online image. However, Professor Viktor MayerSchönberger, an expert from Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, said that Google cannot escape compliance with the law of France implementing the decision of the European

3

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN Court of Justice in 2014 on the right to be forgotten. Mayer-Schönberger said nations, including the US, had long maintained that their local laws have "extra-territorial effects"2

What is the scope of personal data? The new proposed EU regulations define personal data in art 4 as follows: “(1) 'data subject' means an identified natural person or a natural person who can be identified, directly or indirectly, by means reasonably likely to be used by the controller or by any other natural or legal person, in particular by reference to an identification number, location data, online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that person; (2) 'personal data' means any information relating to a data subject.” Data protection directive9, definitions in art. 2 are “(a) 'personal data' shall mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity.” These definitions define personal data broadly as information that can be linked, either by itself or in combination with other available information, to uniquely identify a natural person. However, they leave to interpretation whether it includes information that can be used to identify a person with high probability but not with certainty, e.g. a picture of a person or an account of a person’s history, actions of performance. Neither is it clear whether it includes information that identifies a person not uniquely, but as a member of a more or less small set of individuals, such as a family. A related question is how aggregated and derived forms of information (e.g. statistics) should be affected when some of the raw data from which statistics are derived are forgotten. Removing forgotten information from all aggregated or derived forms may present a significant technical challenge. On the other hand, not removing such information from aggregated forms is risky, because it may be possible to infer the forgotten raw information by correlating different aggregated forms. 2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_be_forgotten

4

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN The difficulty is that the EU regulations and laws tend to be deliberately broad and general, to allow for a range of interpretations appropriate for many different situations. However, technical means to ensure the right to be forgotten require a precise definition of the data and circumstances to which the right to be for forgotten shall apply.

Who has the right to request deletion of a data item? Next, we consider the question of who has the right to request deletion of a data item. In many cases, the answer is unambiguous, such as when a person requests that their own name, date-of-birth and residential address are removed from a database. In other cases, however, the question of who has the right to demand that an item should be forgotten is subject to interpretation. For instance, consider a photograph depicting Alice and Bob engaged in some activity at a given time and place. Suppose Alice wishes the photo to be forgotten, while Bob insists that it persist. Whose wishes should be respected? What if multiple people appear in a group photo? Who gets to decide if and when the photo should be forgotten? In another example, Bob incorporates part of a tweet he receives from Alice into a longer blog post of his own. When Alice later exercises her right to remove her tweet, what effect does this have on the status of Bob’s blog post? Does Bob have to remove his entire blog post? Does he have to remove Alice’s tweet from it and rewrite his post accordingly? What criteria should be used to decide? A related question is how the right to be forgotten should be balanced against the public interest in accountability, journalism, history, and scientific inquiry? Should a politician or government be able to request removal of some embarrassing reports? Should the author of a scientific study be able to request withdrawal of the publication? What principles should be used to decide, and who has the authority to make a decision?

What constitutes “forgetting” a data item? Our next question concerns the question of what is an acceptable way of “forgetting” information. A strict interpretation would require that all copies of the data be erased and removed from any derived or aggregated representations to the point where recovering the 5

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN data is impossible by any known technical means. A slightly weaker (and possibly more practical) interpretation would allow encrypted copies of the data to survive, as long as they cannot be deciphered by unauthorized parties. An even weaker (and more practical) interpretation would allow clear text copies of the data to survive, as long as the data would no longer appear in public indices, database query results, or in the results of search engines.

The European Union Perspective and the United States Perspective

The European Union Perspective The EU formally recognized privacy as a fundamental human right after the Second World War, when several countries started liberating themselves from the oppressive regimes led by the fascist and communist ideologies. The enactments of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as well as the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) at international level have prompted EU Member States to enact legislation in order to implement the principles these acts were proclaiming. Contrary to the US that does not have privacy included in its Constitution, and not a horizontal regulation to protect it, the EU later formally recognized the right to privacy as an underlying, defining element of the common space it aims at creating. The Lisbon Treaty explicitly protects privacy as a fundamental right of EU citizens, and so does the EU Charter of the Fundamental Rights (EUCFR) that goes even further and also establishes the right to protection of personal rights and freedom in the processing of data as a fundamental rights. This structure represents the basis for the recognition of a right to be forgotten by the CJEU, in the famous Google SpainCosteja ruling. One might ask why specifically Europe as opposed to the US was the jurisdiction to develop such a strong privacy protective framework given that for centuries it was the US that was defined as the biggest democracy protective of individual liberties. Nonetheless, the general sensitivity of European countries is grounded in their historic and cultural background, which has shaped their attitudes towards an over-stepping state or over-intruding private

6

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN corporations. Their past made them understand and cherish the value of privacy, having “recently seen the evil that flourishes when privacy is not protected”

The United States Perspective Following the CJEU decision and the events that followed, as well as other privacy-related developments taking place worldwide, The United States saw themselves caught in the middle of a massive campaign to address privacy matters. With the European Union having declared its intention to enact “more effective and standardized data privacy laws across Europe”, the US framework in place was being questioned. The broader debate on where exactly one should draw the line between right to privacy and the freedom to speech became pivotal for the understanding and appraisal of the right to be forgotten. While some have criticized the European approach, others have acclaimed its adequacy and thus lobbied for similar strategy. The US vision on privacy and personal data has long time been conflicting with the European view. While the general EU Member States’ vision is focused on the individual and his rights, validating state intervention to ensure one’s public persona, the United States applies a market-focused strategy, with voluntary code of conduct, creating a less centralized legislative framework, with subject specific rules, where the aim is to reduce intrusions by the state. Europe considers personal data as an essential part of an individual’s liberty, being more prone to accepting a right to be forgotten, while the United States is known for having a wide preference for disclosure, often offering privacy less weight than to interests that are more “necessary to protect”, such as national security. In this context if there is or could be a right to be forgotten in the US represents a fundamental element of the debate on privacy versus free speech, specifically regarding the resolution of conflicts their clash might entail, as well as concerning limitations the state is empowered to impose on the right to privacy and how efficient it is in protecting its citizens. Irrespective of the outcome of this debate, there is one element that is clear: the official recognition of the right to be forgotten by its transatlantic neighbour has revealed the deep flaws in the American Society, causing harsh reaction on both sides. These flaw will have to be addressed eventually, thus state and court intervention will be required. In this context, the implementation of an EU right to be forgotten might just be a valid solution. However, if it would lead to evolution or regress, only time could tell.

7

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Criticism Major criticisms stem from the idea that the right to be forgotten would restrict the right to freedom of speech. Many nations, and the United States in particular (with the First Amendment to the United States Constitution), have very strong domestic freedom of speech law, which would be challenging to reconcile with the right to be forgotten. Some academics see that only a limited form of the right to be forgotten would be reconcilable with US constitutional law; the right of an individual to delete data that he or she has personally submitted. In this limited form of the right individuals could not have material removed that has been uploaded by others, as demanding the removal of information could constitute censorship and a reduction in the freedom of expression in many countries. Sandra Coliver of the Open Society Justice Initiative argues that not all rights must be compatible and this conflict between the two rights is not detrimental to the survival of either. The Proposed Data Protection Regulation is written broadly and this has caused concern. It has attracted criticism that its enactment would require data controlling companies to go to great lengths to identify third parties with the information and remove it. The Proposed Regulation has also attracted criticism due to the fact that this could produce a censoring effect in that companies, such as Facebook or Google, will wish to not be fined under the act, and will therefore be likely to delete wholesale information rather than facing the fine, which could produce a "serious chilling effect." In addition to this, there are concerns about the requirement to take down information that others have posted about an individual; the definition of personal data in Article 4(2) includes "any information relating to" the individual. This, critics have claimed, would require companies to take down any information relating to an individual, regardless of its source, which would amount to censorship, and result in the big data companies eradicating a lot of data to comply with this.[98] Such removal can impact the accuracy and ability of businesses and individuals to carry out business intelligence, particularly due diligence to comply with antibribery, anticorruption, and know your customer laws. The right to be forgotten was invoked to remove from Google searches 120 reports about company directors published by Dato Capital, a Spanish company which compiles such reports about private company directors, consisting entirely of information they are required by law to disclose; Fortune magazine examined the 64 reports relating to UK directorships, finding that in 27 (42%) the director was the only person named, in the remaining only the director and co-directors were named, and 23 (36%) involve directorships started since 2012. 8

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN Other criticism revolves around the principle of accountability. There are concerns that the Proposed Data Protection Act will result in Google and other Internet search engines not producing neutral search results, but rather producing biased and patchy results, and compromising the integrity of Internet-based information. To balance out this criticism, the Proposed Data Protection Regulation includes an exception "for the processing of personal data carried out solely for journalistic purposes or the purpose of artistic or literary expression in order to reconcile the right to the protection of personal data with the rules governing freedom of expression." Article 80 upholds freedom of speech, and while not lessening obligations on data providers and social media sites, nevertheless due to the wide meaning of "journalistic purposes" allows more autonomy and reduces the amount of information that is necessary to be removed. When Google agreed to implement the ruling, European Commission Vice-President Viviane Reding said, "The Court also made clear that journalistic work must not be touched; it is to be protected." However, Google was criticized for taking down (under the Costeja precedent) a BBC News blog post about Stan O'Neal by economics editor Robert Peston (eventually, Peston reported that his blog post has remained findable in Google after all). Despite these criticisms and Google’s action, the company’s CEO, Larry Page worries that the ruling will be “used by other governments that aren’t as forward and progressive as Europe to do bad things", though has since distanced himself from that position. For example, pianist Dejan Lazic cited the Right To Be Forgotten in trying to remove a negative review about his performance from The Washington Post. He claimed that the critique was "defamatory, mean-spirited, optionated, offensive and simply irrelevant for the arts". and the St. Lawrence parish of the Roman Catholic church in Kutno, Poland asked Google to remove the Polish Wikipedia page about it, without any allegations mentioned therein as of that date. Index on Censorship claimed that the Costeja ruling "allows individuals to complain to search engines about information they do not like with no legal oversight. This is akin to marching into a library and forcing it to pulp books. Although the ruling is intended for private individuals it opens the door to anyone who wants to whitewash their personal history....The Court's decision is a retrograde move that misunderstands the role and responsibility of search engines and the wider internet. It should send chills down the spine of everyone in the European Union who believes in the crucial importance of free expression and freedom of information."

9

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN In 2014, the Gerry Hutch page on the English Wikipedia was among the first Wikipedia pages to be removed by several search engines' query results in the European Union. The Daily Telegraph said, on 6 Aug 2014, that Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales "described the EU's Right to be Forgotten as deeply immoral, as the organisation that operates the online encyclopedia warned the ruling will result in an internet riddled with memory holes". Other commentators have disagreed with Wales, pointing to problems such as Google including links to revenge porn sites in its search results, and have accused Google of orchestrating a publicity campaign to escape the burdensome obligation to comply with the law. Julia Powles, a law and technology researcher at the University of Cambridge, made a rebuttal to Wales' and the Wikimedia Foundation concerns in an editorial published by Guardian, opining that "There is a public sphere of memory and truth, and there is a private one...Without the freedom to be private, we have precious little freedom at all." In response to the criticism, the EU has released a factsheet to address what it considers myths about the right to be forgotten

AGAINST EU data protection rules

FOR EU data protection rules

1. INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY Individuals need to take greater responsibility for the personal data they upload online. Nobody is forcing individuals to upload personal information to social networking sites. The new EU data protection rules promise to deliver more than is practical. By taking responsibility away from individuals and replacing it with a legal framework, they may create unreasonable expectations for privacy

1. MORE EFFICIENT The existing rules are confusing, with different legal jurisdictions claiming their (often contradictory) laws all apply at the same time. Under the new rules, businesses would follow one set of data protection rules: the rules of their country of establishment within the EU.

and a false sense of safety and security online. 2. IMPRACTICAL

2. NEW TECHNOLOGY

The so-called “right to be forgotten” is a much- Technology moves fast. Much of the existing

10

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN heralded part of the new data protection rules,

set of data protection rules was drawn up in

but is it realistic? Once something has been

the nineties, before the current trend for

published online then it can be cached,

social networking and high-speed internet

archived, reposted and replicated in a thousand had taken off. different places across the internet. At what point does privacy become censorship? How much should the “right to be forgotten” be balanced with everybody else’s “right to remember”.

3. ONEROUS The cost of implementing the new rules will fall disproportionately on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Larger companies will be better equiped to absorb the costs of the regulations. As SMEs account for 60% of Europe’s GDP, do we want to throw even more red tape at them during a recession?

3. FREEDOM OF SPEECH Despite what critics might argue, the new rules in no way threaten freedom of speech. Instead, it strengthens individual rights by clarifying exactly what rights an individual has with regards to the data they have personally uploaded. It does not grant individuals the right to order others to take down information they disagree with.

11

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

CONCLUSIONS On 13th May 2013, the CJEU rendered a remarkable decision in the history of the data protection. By formally recognizing the existence of the right to be forgotten in the EU legislative framework, it clarified the position the EU market should take a vis-a-vis personal data and privacy, its effects being vital for the evolution of privacy regulations. However one element is clear, unless a unitary approach to the existence and implementation of the right is adopted, the differences in vision between the US and EU societies will exacerbate, leading to both the intensification of already existing problems, as well as emergence of new ones. Implementation of laws may become not only inconsistent from one jurisdiction to another , because of that, it would turn law into a territory of unpredictability and uncertainty. This would lead to unjustified differences in the way individuals and private entities are treated, decreasing the overall trust in the legal system. The market would also be harmed, as companies may be forced to take undesired measured in order to comply with the discrepancies(e.g. moving one country to another). Admittedly, several further questions could and may be should be asked, such as whether a right to be forgotten should exist at all, whether a harmonization of legal perspectives would be desirable, etc. More time and research are needed in the following years in order to answer these questions and, specifically, assess the rightfulness of having a right to be forgotten. If, when, and how this right should and or would be adopted is at the governments’ and courts’ discretion. It is only later that the effects of the CJEU Google Spain-Costeja ruling will allow an adequate assessment of its rightfulness, and further right to be forgotten’s fate will be easier to appraise.

12

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

WEBLIOGRAPHY

www.cyberlaw.com www.cyberlawsindia.net www.indlii.org www.cyberlawassociation.com www.ibef.org www.answers.com www.vakilno1.com

13

CYBER LAW PROJECT “RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN” PROJECT SUBMITTED TO: MRS. DEBMITA MONDAL (ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF CYBER LAW)

PROJECT SUBMITTED BY: RAHUL MANDAVI Semester VII, Section A

ROLL NO. 125 SUBMITTED ON: 26.09.2016

HIDAYATULLAH NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Contents Declaration .............................................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ iii Aims and Objectives .............................................................................................................................. iv Research Methodology ........................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 What is Right to be Forgotten ................................................................................................................. 2 The European Union Perspective and the United States Perspective ..................................................... 6 Criticism.................................................................................................................................................. 8 CONCLUSIONS................................................................................................................................... 12 WEBLIOGRAPHY............................................................................................................................... 13

i

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Declaration

I hereby declare that this research work titled “RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN” is my own work and represents my own ideas, and where others’ ideas or words have been included, I have adequately cited and referenced the original sources. I also declare that I have adhered to all principles of academic honesty and integrity and have not misrepresented or fabricated or falsified any idea/data/fact/source in my submission.

(RAHUL MANDAVI)

ii

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Acknowledgements

I, Rahul Mandavi, would like to humbly present this project to MRS. DEBMITA MONDAL. I would first of all like to express my most sincere gratitude to MRS. DEBMITA MONDAL for her encouragement and guidance regarding several aspects of this project. I am thankful for being given the opportunity of doing a project on ‘RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN’. I am thankful to the library staff as well as the IT lab staff for all the conveniences they have provided me with, which have played a major role in the completion of this paper. I would like to thank God for keeping me in good health and senses to complete this project. Last but definitely not the least, I am thankful to my seniors for all their support, tips and valuable advice whenever needed. I present this project with a humble heart.

- RAHUL MANDAVI SEMESTER VII, SECTION A, ROLL NUMBER 125 BA.LLB (HONS.)

iii

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Aims and Objectives

I.

To understand what is Right to be Forgotten.

II.

To understand the EU perspective and US perspective

III.

To understand the Criticism of right to be forgotten .

iv

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Research Methodology

Nature of Research This research work is descriptive in nature. It describes the perspective of Right to be Forgotten.

Sources of Data This study is done with the help of secondary data. This secondary information has been obtained from published sources such as books, journals, websites, newspapers, research works etc.

v

INTRODUCTION

Mario Costeja González spent five years fighting to have 18 words delisted from Google search results on his name. When the Spaniard googled himself in 2009, two prominent results appeared: homeforeclosure notices from 1998, when he was in temporary financial trouble. The notices had been published in Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia and recently digitised. But their original purpose – attracting buyers to auction – had lapsed a decade ago, as had the debt. Costeja González asked the newspaper to remove them. When that was unsuccessful, he challenged Google, and the case was eventually elevated to the European Court of Justice, Europe’s highest court. Forgetting and remembering are complex, messy, human processes. Our minds reconstruct, layer, contextualise and sediment. The worldwide web is different. As Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page described in their original Stanford research paper, the web is “a vast collection of completely uncontrolled heterogeneous documents”. And search engines take that corpus and give it perpetual, decontextualised freshness. Vast catalogues of human sentiments and stories get served up at the mercurial whims of black box algorithms – algorithms that Brin and Page initially described as “inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers”, in a way that is “difficult even for experts to evaluate” and therefore is “particularly insidious”. The crude, timeless nature of digital memory – and the unquestioned power of private, commercially motivated companies that control it – was a challenge that 59-year-old Costeja González decided to tackle directly.1

1

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/feb/18/the-right-be-forgotten-google-search

1

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

What is Right to be Forgotten

The right to be forgotten is a concept discussed and put into practice in the European Union (EU) and Argentina since 2006. The issue has arisen from desires of individuals to "determine the development of their life in an autonomous way, without being perpetually or periodically stigmatized as a consequence of a specific action performed in the past." There has been controversy about the practicality of establishing a right to be forgotten to the status of an international human right in respect to access to information, due in part to the vagueness of current rulings attempting to implement such a right. There are concerns about its impact on the right to freedom of expression, its interaction with the right to privacy, and whether creating a right to be forgotten would decrease the quality of the Internet through censorship and a rewriting of history, and opposing concerns about problems such as revenge porn sites appearing in search engine listings for a person's name, or references to petty crimes committed many years ago indefinitely remaining an unduly prominent part of a person's Internet footprint.

Conception and proposal Europe’s data protection laws are intended to secure potentially damaging, private information about individuals. The notion of "the right to be forgotten" is derived from numerous pre-existing European ideals. There is a longstanding belief in the United Kingdom, specifically under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act, that after a certain period of time, many criminal convictions are “spent”, meaning that information regarding said person should not be regarded when obtaining insurance or seeking employment. Similarly, France values this right - le droit d’oubli (the right to be forgotten). It was officially recognized in French Law in 2010. Views on the right to be forgotten differ greatly between America and EU countries. In America, transparency, the right of free speech according to the First Amendment, and the right to know have typically been favoured over the obliteration of truthfully published information regarding individuals and corporations. The term "right to be forgotten" is a relatively new idea, though on May 13, 2014 the European Court of Justice 2

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN legally solidified that the "right to be forgotten” is a human right when they ruled against Google in the Costeja case. In 1995 the European Union adopted the European Data Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC) to regulate the processing of personal data. This is now considered a component of human rights law. The new European Proposal for General Data Protection Regulation provides protection and exemption for companies listed as "media" companies, like newspapers and other journalistic work. However, Google purposely opted out of being classified as a "media" company and so is not protected. Judges in the European Union ruled that because the international corporation, Google, is a collector and processor of data it should be classified as a "data controller" under the meaning of the EU data protection directive. These "data controllers" are required under EU law to remove data that is "inadequate, irrelevant, or no longer relevant", making this directive of global importance.

Current legal frameworks The right to be forgotten "reflects the claim of an individual to have certain data deleted so that third persons can no longer trace them." It has been defined as "the right to silence on past events in life that are no longer occurring." The right to be forgotten leads to allowing individuals to have information, videos or photographs about themselves deleted from certain internet records so that they cannot be found by search engines. As of 2014 there are few protections against the harm that incidents such as revenge porn sharing, or pictures uploaded due to poor judgement, can do. The right to be forgotten is distinct from the right to privacy, due to the distinction that the right to privacy constitutes information that is not publicly known, whereas the right to be forgotten involves removing information that was publicly known at a certain time and not allowing third parties to access the information. Limitations of application in a jurisdiction include the inability to require removal of information held by companies outside the jurisdiction. There is no global framework to allow individuals control over their online image. However, Professor Viktor MayerSchönberger, an expert from Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, said that Google cannot escape compliance with the law of France implementing the decision of the European

3

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN Court of Justice in 2014 on the right to be forgotten. Mayer-Schönberger said nations, including the US, had long maintained that their local laws have "extra-territorial effects"2

What is the scope of personal data? The new proposed EU regulations define personal data in art 4 as follows: “(1) 'data subject' means an identified natural person or a natural person who can be identified, directly or indirectly, by means reasonably likely to be used by the controller or by any other natural or legal person, in particular by reference to an identification number, location data, online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that person; (2) 'personal data' means any information relating to a data subject.” Data protection directive9, definitions in art. 2 are “(a) 'personal data' shall mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity.” These definitions define personal data broadly as information that can be linked, either by itself or in combination with other available information, to uniquely identify a natural person. However, they leave to interpretation whether it includes information that can be used to identify a person with high probability but not with certainty, e.g. a picture of a person or an account of a person’s history, actions of performance. Neither is it clear whether it includes information that identifies a person not uniquely, but as a member of a more or less small set of individuals, such as a family. A related question is how aggregated and derived forms of information (e.g. statistics) should be affected when some of the raw data from which statistics are derived are forgotten. Removing forgotten information from all aggregated or derived forms may present a significant technical challenge. On the other hand, not removing such information from aggregated forms is risky, because it may be possible to infer the forgotten raw information by correlating different aggregated forms. 2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_be_forgotten

4

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN The difficulty is that the EU regulations and laws tend to be deliberately broad and general, to allow for a range of interpretations appropriate for many different situations. However, technical means to ensure the right to be forgotten require a precise definition of the data and circumstances to which the right to be for forgotten shall apply.

Who has the right to request deletion of a data item? Next, we consider the question of who has the right to request deletion of a data item. In many cases, the answer is unambiguous, such as when a person requests that their own name, date-of-birth and residential address are removed from a database. In other cases, however, the question of who has the right to demand that an item should be forgotten is subject to interpretation. For instance, consider a photograph depicting Alice and Bob engaged in some activity at a given time and place. Suppose Alice wishes the photo to be forgotten, while Bob insists that it persist. Whose wishes should be respected? What if multiple people appear in a group photo? Who gets to decide if and when the photo should be forgotten? In another example, Bob incorporates part of a tweet he receives from Alice into a longer blog post of his own. When Alice later exercises her right to remove her tweet, what effect does this have on the status of Bob’s blog post? Does Bob have to remove his entire blog post? Does he have to remove Alice’s tweet from it and rewrite his post accordingly? What criteria should be used to decide? A related question is how the right to be forgotten should be balanced against the public interest in accountability, journalism, history, and scientific inquiry? Should a politician or government be able to request removal of some embarrassing reports? Should the author of a scientific study be able to request withdrawal of the publication? What principles should be used to decide, and who has the authority to make a decision?

What constitutes “forgetting” a data item? Our next question concerns the question of what is an acceptable way of “forgetting” information. A strict interpretation would require that all copies of the data be erased and removed from any derived or aggregated representations to the point where recovering the 5

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN data is impossible by any known technical means. A slightly weaker (and possibly more practical) interpretation would allow encrypted copies of the data to survive, as long as they cannot be deciphered by unauthorized parties. An even weaker (and more practical) interpretation would allow clear text copies of the data to survive, as long as the data would no longer appear in public indices, database query results, or in the results of search engines.

The European Union Perspective and the United States Perspective

The European Union Perspective The EU formally recognized privacy as a fundamental human right after the Second World War, when several countries started liberating themselves from the oppressive regimes led by the fascist and communist ideologies. The enactments of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as well as the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) at international level have prompted EU Member States to enact legislation in order to implement the principles these acts were proclaiming. Contrary to the US that does not have privacy included in its Constitution, and not a horizontal regulation to protect it, the EU later formally recognized the right to privacy as an underlying, defining element of the common space it aims at creating. The Lisbon Treaty explicitly protects privacy as a fundamental right of EU citizens, and so does the EU Charter of the Fundamental Rights (EUCFR) that goes even further and also establishes the right to protection of personal rights and freedom in the processing of data as a fundamental rights. This structure represents the basis for the recognition of a right to be forgotten by the CJEU, in the famous Google SpainCosteja ruling. One might ask why specifically Europe as opposed to the US was the jurisdiction to develop such a strong privacy protective framework given that for centuries it was the US that was defined as the biggest democracy protective of individual liberties. Nonetheless, the general sensitivity of European countries is grounded in their historic and cultural background, which has shaped their attitudes towards an over-stepping state or over-intruding private

6

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN corporations. Their past made them understand and cherish the value of privacy, having “recently seen the evil that flourishes when privacy is not protected”

The United States Perspective Following the CJEU decision and the events that followed, as well as other privacy-related developments taking place worldwide, The United States saw themselves caught in the middle of a massive campaign to address privacy matters. With the European Union having declared its intention to enact “more effective and standardized data privacy laws across Europe”, the US framework in place was being questioned. The broader debate on where exactly one should draw the line between right to privacy and the freedom to speech became pivotal for the understanding and appraisal of the right to be forgotten. While some have criticized the European approach, others have acclaimed its adequacy and thus lobbied for similar strategy. The US vision on privacy and personal data has long time been conflicting with the European view. While the general EU Member States’ vision is focused on the individual and his rights, validating state intervention to ensure one’s public persona, the United States applies a market-focused strategy, with voluntary code of conduct, creating a less centralized legislative framework, with subject specific rules, where the aim is to reduce intrusions by the state. Europe considers personal data as an essential part of an individual’s liberty, being more prone to accepting a right to be forgotten, while the United States is known for having a wide preference for disclosure, often offering privacy less weight than to interests that are more “necessary to protect”, such as national security. In this context if there is or could be a right to be forgotten in the US represents a fundamental element of the debate on privacy versus free speech, specifically regarding the resolution of conflicts their clash might entail, as well as concerning limitations the state is empowered to impose on the right to privacy and how efficient it is in protecting its citizens. Irrespective of the outcome of this debate, there is one element that is clear: the official recognition of the right to be forgotten by its transatlantic neighbour has revealed the deep flaws in the American Society, causing harsh reaction on both sides. These flaw will have to be addressed eventually, thus state and court intervention will be required. In this context, the implementation of an EU right to be forgotten might just be a valid solution. However, if it would lead to evolution or regress, only time could tell.

7

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

Criticism Major criticisms stem from the idea that the right to be forgotten would restrict the right to freedom of speech. Many nations, and the United States in particular (with the First Amendment to the United States Constitution), have very strong domestic freedom of speech law, which would be challenging to reconcile with the right to be forgotten. Some academics see that only a limited form of the right to be forgotten would be reconcilable with US constitutional law; the right of an individual to delete data that he or she has personally submitted. In this limited form of the right individuals could not have material removed that has been uploaded by others, as demanding the removal of information could constitute censorship and a reduction in the freedom of expression in many countries. Sandra Coliver of the Open Society Justice Initiative argues that not all rights must be compatible and this conflict between the two rights is not detrimental to the survival of either. The Proposed Data Protection Regulation is written broadly and this has caused concern. It has attracted criticism that its enactment would require data controlling companies to go to great lengths to identify third parties with the information and remove it. The Proposed Regulation has also attracted criticism due to the fact that this could produce a censoring effect in that companies, such as Facebook or Google, will wish to not be fined under the act, and will therefore be likely to delete wholesale information rather than facing the fine, which could produce a "serious chilling effect." In addition to this, there are concerns about the requirement to take down information that others have posted about an individual; the definition of personal data in Article 4(2) includes "any information relating to" the individual. This, critics have claimed, would require companies to take down any information relating to an individual, regardless of its source, which would amount to censorship, and result in the big data companies eradicating a lot of data to comply with this.[98] Such removal can impact the accuracy and ability of businesses and individuals to carry out business intelligence, particularly due diligence to comply with antibribery, anticorruption, and know your customer laws. The right to be forgotten was invoked to remove from Google searches 120 reports about company directors published by Dato Capital, a Spanish company which compiles such reports about private company directors, consisting entirely of information they are required by law to disclose; Fortune magazine examined the 64 reports relating to UK directorships, finding that in 27 (42%) the director was the only person named, in the remaining only the director and co-directors were named, and 23 (36%) involve directorships started since 2012. 8

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN Other criticism revolves around the principle of accountability. There are concerns that the Proposed Data Protection Act will result in Google and other Internet search engines not producing neutral search results, but rather producing biased and patchy results, and compromising the integrity of Internet-based information. To balance out this criticism, the Proposed Data Protection Regulation includes an exception "for the processing of personal data carried out solely for journalistic purposes or the purpose of artistic or literary expression in order to reconcile the right to the protection of personal data with the rules governing freedom of expression." Article 80 upholds freedom of speech, and while not lessening obligations on data providers and social media sites, nevertheless due to the wide meaning of "journalistic purposes" allows more autonomy and reduces the amount of information that is necessary to be removed. When Google agreed to implement the ruling, European Commission Vice-President Viviane Reding said, "The Court also made clear that journalistic work must not be touched; it is to be protected." However, Google was criticized for taking down (under the Costeja precedent) a BBC News blog post about Stan O'Neal by economics editor Robert Peston (eventually, Peston reported that his blog post has remained findable in Google after all). Despite these criticisms and Google’s action, the company’s CEO, Larry Page worries that the ruling will be “used by other governments that aren’t as forward and progressive as Europe to do bad things", though has since distanced himself from that position. For example, pianist Dejan Lazic cited the Right To Be Forgotten in trying to remove a negative review about his performance from The Washington Post. He claimed that the critique was "defamatory, mean-spirited, optionated, offensive and simply irrelevant for the arts". and the St. Lawrence parish of the Roman Catholic church in Kutno, Poland asked Google to remove the Polish Wikipedia page about it, without any allegations mentioned therein as of that date. Index on Censorship claimed that the Costeja ruling "allows individuals to complain to search engines about information they do not like with no legal oversight. This is akin to marching into a library and forcing it to pulp books. Although the ruling is intended for private individuals it opens the door to anyone who wants to whitewash their personal history....The Court's decision is a retrograde move that misunderstands the role and responsibility of search engines and the wider internet. It should send chills down the spine of everyone in the European Union who believes in the crucial importance of free expression and freedom of information."

9

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN In 2014, the Gerry Hutch page on the English Wikipedia was among the first Wikipedia pages to be removed by several search engines' query results in the European Union. The Daily Telegraph said, on 6 Aug 2014, that Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales "described the EU's Right to be Forgotten as deeply immoral, as the organisation that operates the online encyclopedia warned the ruling will result in an internet riddled with memory holes". Other commentators have disagreed with Wales, pointing to problems such as Google including links to revenge porn sites in its search results, and have accused Google of orchestrating a publicity campaign to escape the burdensome obligation to comply with the law. Julia Powles, a law and technology researcher at the University of Cambridge, made a rebuttal to Wales' and the Wikimedia Foundation concerns in an editorial published by Guardian, opining that "There is a public sphere of memory and truth, and there is a private one...Without the freedom to be private, we have precious little freedom at all." In response to the criticism, the EU has released a factsheet to address what it considers myths about the right to be forgotten

AGAINST EU data protection rules

FOR EU data protection rules

1. INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY Individuals need to take greater responsibility for the personal data they upload online. Nobody is forcing individuals to upload personal information to social networking sites. The new EU data protection rules promise to deliver more than is practical. By taking responsibility away from individuals and replacing it with a legal framework, they may create unreasonable expectations for privacy

1. MORE EFFICIENT The existing rules are confusing, with different legal jurisdictions claiming their (often contradictory) laws all apply at the same time. Under the new rules, businesses would follow one set of data protection rules: the rules of their country of establishment within the EU.

and a false sense of safety and security online. 2. IMPRACTICAL

2. NEW TECHNOLOGY

The so-called “right to be forgotten” is a much- Technology moves fast. Much of the existing

10

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN heralded part of the new data protection rules,

set of data protection rules was drawn up in

but is it realistic? Once something has been

the nineties, before the current trend for

published online then it can be cached,

social networking and high-speed internet

archived, reposted and replicated in a thousand had taken off. different places across the internet. At what point does privacy become censorship? How much should the “right to be forgotten” be balanced with everybody else’s “right to remember”.

3. ONEROUS The cost of implementing the new rules will fall disproportionately on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Larger companies will be better equiped to absorb the costs of the regulations. As SMEs account for 60% of Europe’s GDP, do we want to throw even more red tape at them during a recession?

3. FREEDOM OF SPEECH Despite what critics might argue, the new rules in no way threaten freedom of speech. Instead, it strengthens individual rights by clarifying exactly what rights an individual has with regards to the data they have personally uploaded. It does not grant individuals the right to order others to take down information they disagree with.

11

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

CONCLUSIONS On 13th May 2013, the CJEU rendered a remarkable decision in the history of the data protection. By formally recognizing the existence of the right to be forgotten in the EU legislative framework, it clarified the position the EU market should take a vis-a-vis personal data and privacy, its effects being vital for the evolution of privacy regulations. However one element is clear, unless a unitary approach to the existence and implementation of the right is adopted, the differences in vision between the US and EU societies will exacerbate, leading to both the intensification of already existing problems, as well as emergence of new ones. Implementation of laws may become not only inconsistent from one jurisdiction to another , because of that, it would turn law into a territory of unpredictability and uncertainty. This would lead to unjustified differences in the way individuals and private entities are treated, decreasing the overall trust in the legal system. The market would also be harmed, as companies may be forced to take undesired measured in order to comply with the discrepancies(e.g. moving one country to another). Admittedly, several further questions could and may be should be asked, such as whether a right to be forgotten should exist at all, whether a harmonization of legal perspectives would be desirable, etc. More time and research are needed in the following years in order to answer these questions and, specifically, assess the rightfulness of having a right to be forgotten. If, when, and how this right should and or would be adopted is at the governments’ and courts’ discretion. It is only later that the effects of the CJEU Google Spain-Costeja ruling will allow an adequate assessment of its rightfulness, and further right to be forgotten’s fate will be easier to appraise.

12

RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN

WEBLIOGRAPHY

www.cyberlaw.com www.cyberlawsindia.net www.indlii.org www.cyberlawassociation.com www.ibef.org www.answers.com www.vakilno1.com

13

Related Documents

Right To Be Forgotten Cyber Law

February 2021 0

Right To Practice Law

January 2021 0

Common Law Right To Travel

January 2021 1

Cyber Law - 16167

February 2021 0

Cyber Law Chhagan

February 2021 2

Right To Travel

January 2021 1More Documents from "BMWmom"

100 Ways To Kill Your Business

February 2021 0

25kvisitorspermonth_backlinko

February 2021 3

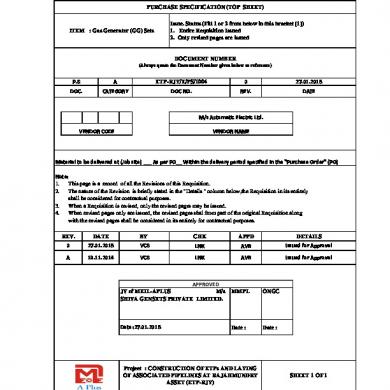

Rev 0 Ps For Gg Set1

January 2021 2

Air Separation Ppt

March 2021 0

15139_bangun Pemudi Pemuda

February 2021 0