Project I - English I Movie Review

This document was uploaded by user and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this DMCA report form. Report DMCA

Overview

Download & View Project I - English I Movie Review as PDF for free.

More details

- Words: 1,908

- Pages: 9

Loading documents preview...

Movie review

EXAMINING ‘ZOOTOPIA’: CASTE-BASED GHETTOIZATION IN MODERN INDIA SUBJECT: LAW AND LANGUAGE

SUBMITTED TO: DR. UMA MAHESHWARI CHIMIRALA SUBMITTED BY: NATASHA SINGH, 2019-5LLB-88 YEAR 1, SEMESTER 1

CONTENTS 1

Introduction.........................................................................................................................1

2

Legal Themes: Caste Ghettoization....................................................................................4

3

Conclusion..........................................................................................................................6

1

INTRODUCTION Zootopia released in 2016 to widespread critical acclaim. The title is a portmanteau of

the Latin root zoo-, meaning ‘living-being’ or ‘animal’, and the sociological concept ‘utopia’, which represents an ideal or perfect society. Likened to George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), the story centres on a futuristic society of anthropomorphic animals, set in an advanced time where animals have learnt to coexist peacefully. The protagonist of the story is a spunky rabbit, Judy, who dreams of becoming the first bunny police-officer. She is drawn into an investigation of violent crimes being perpetrated by the previously-civilised predators against prey. Like Animal Farm before it, Zootopia uses species/families of animals to represent the distinct classes in society. Predictably, the ‘lower’ classes of animals symbolise the traditionally marginalized communities, while the predators occupy positions of power, influence, and importance. Zootopia executes this concept while maintaining fidelity to the natural status quo: a carnivorous predator is outnumbered ten-to-one by its herbivorous prey. This means that the timorous grass-eaters comprise the bulk of the electorate in the fictional land where these mammals dwell, effectively turning the food chain on its head. Perhaps more importantly, Zootopia, like its literary predecessor, satirizes the broader political setting of the day. Orwell, who felt a strong distaste for what he felt was the ideologically bankrupt UK-USSR alliance, stated he wrote Animal Farm with a “full consciousness”1, intending “to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole.”2 Similarly, critics deconstructing Zootopia have commended the film’s “smart, funny and thought-provoking”3 message. Zootopia was reviewed by the American film-critic Peter Travers for Rolling Stone, the Indian journalist Reagan Gavin Rasquinha for The Times of India, and the British filmcritic John Nugent for Empire. Interestingly, all three different reviews analyzed Zootopia differently. The critics recognized that Zootopia has a hidden message; they were simply divided over what it was. Considering that the movie was an American production, many felt the central theme of fear, alienation and xenophobia was a thinly-veiled reference to the 11

George Orwell, Why I Write, GANGREL, Summer 1946. Id. 3 Neil Genzlinger, Review: In ‘Zootopia,’ an Intrepid Country Bunny Chases Her Dreams In The Big City, THE NEW YORK TIMES, March 23, 2016 at page 6, Section C. 2

1

politically charged climate of the divisive presidential-election. In his Rolling Stones review, Travers described Zootopia as a “subversive”4 movie that “put a lot on its animated plate”,5 interpreting its depiction of the treatment of meat-eating species as potential threats as an analogue to the US government’s notorious policy on racial-profiling. In the UK, where it was released under the alternative title Zootropolis, Empire magazine praised the movie for its rich detailing, acknowledging the uneasy onscreen predator-prey relationship as a “smart analogy for the debates on immigration that rage in our human world”6. While Rasquinha avoided explicitly politicizing the movie, he complimented it as an “intelligent”7 movie which avoided being “too moralistic”8 about weighty issues. Due to the wide scope of interpretation, and the marketing of Zootopia as a children’s movie, a majority of the reviews eschewed focusing solely on the socio-political issues the film touched upon, and instead lauded its core message of acceptance, rationality, and tolerance. When examined in a specifically Indian context, several points of interest crop up. The film experiments with a variety of themes that have legal and social significance. These include ghettoization, vertical occupational legacy, social pigeonholing, and institutionalized discrimination. Caste-like stratifications, particularly with reference to occupational heredity and endogamy, are strikingly ubiquitous. Japan, too, for example, had a highly inflexible system of social stratification (mibunsei) during the Edo period (1603-1868). Mibunsei was based on a Confucian conception of ‘moral purity’. Those who bore arms and protected others (samurais) were accorded the highest respect in society, followed by peasants and artisans, who produced goods and services. Last of all were the merchant-bankers, who dealt with wealth and money (typically viewed as corrupting influences). Parallel to the Indian Varnasystem, there were also those outside this system entirely. These outcast groups included Burakumin, who carried out the traditionally ‘tainted’ professions (undertaking, gravedigging, scavenging, etc.) The word Burakumin itself literally translates to “village people” or “hamlet people”, a testament to how severely they were physically segregated 4

Peter Travers, ‘Zootopia’ Movie Review, ROLLING STONE (Mar. 3, 2016, 2:22pm ET), https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-reviews/zootopia-92993. 5 Id. 6 John Nugent, Zootropolis Review, EMPIRE ONLINE (Mar. 18, 2016), https://www.empireonline.com/movies/reviews/zootropolis-review. 7 Reagan Gavin Rasquinha, Zootopia Movie Review, THE TIMES OF INDIA (May 9, 2016, 02.34pm IST), https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/english/movie-reviews/zootopia/moviereview/51238901.cms. 8 Id. 2

from mainstream society. The Burakumin scholar Nakagami Kenji analysed the experiences of the Burakumin relative to the other “marginalized outcastes”, noting that the routine exclusion of subaltern communities from the dominant-hegemonic socio-political processes systematically denied their beliefs, feelings, and experiences.9

9

Machiko Ishikawa, Nakagami Kenji’s ‘Writing Back to the Centre’ through the Subaltern Narrative: Reading the Hidden Outcast Voice in ‘Misaki’ and Karekinada, Volume 5, NEW VOICES, 1, 2-3 (2011). 3

1

LEGAL THEMES: CASTE GHETTOIZATION Judy, the protagonist, lives in the rural Bunnyburrow, an overpopulated village inhabited

exclusively by rabbits and hares. As the movie progresses, we see that the degree of segregation is extreme. Gerbils, hamsters, and other rodents dwell in Little Rodentia. Smaller animals prefer to live well away from the larger, more dangerous ones. Judy is desperate to escape the oppressive banality of her hometown to the relatively cosmopolitan capital Zootopia. The Oxford Dictionary defines a ghetto as “a part of a city, especially a slum area, occupied by a minority group or groups”, or alternatively as “an isolated group or area.” The definition, even in a non-sociological context, is suggestive of a level of segregation that forces certain members of society to live apart from the others. The first recorded use of the term was in the early 1700s, with reference to the infamous Venetian Jewish Ghetto. The word may have been derived from the Latin phrase Giudaicetum, which literally translates to ‘Jewish enclave’, or alternatively, from the Germanic-Italian word borghetto (the root of the English word borough), meaning ‘little town’.10 Despite the supposed European etymological origin of the word, the phenomenon of a ghetto, particularly a Dalit one, is oft-seen in Indian cities and villages. Fa Xian, the ChineseBuddhist traveler who wrote an account of early 5 th century India, observed that the Chandala caste, traditionally regarded as ‘impure’ or ‘evil by karma’, was made to live on the outskirts of the town or the village. 11 Centuries of deep-seated dogma, including the persistent belief that any form of contact, however minimal, with a Dalit would ‘pollute’ the upper-caste Hindus ensured that Dalits could only reside in small clusters of hamlets at a prescribed distance from the town temple, lake, and market. In other settlements with a sizeable Dalit population, the lower-castes were forced to use different wells, footpaths, and roads constructed exclusively for their use.

10

Camila Domonoske, Segregated From Its History, How 'Ghetto' Lost Its Meaning, NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO (Apr. 27, 2014, 12:46pm ET), https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/04/27/306829915/segregatedfrom-its-history-how-ghetto-lost-its-meaning. 11 RONALD MELLOR & AMANDA H. PODANY, THE WORLD IN ANCIENT TIMES: PRIMARY SOURCES AND REFERENCE VOLUME 76-77 (Oxford University Press 2005). 11

4

Many believe that the problem of ghettoization has since shifted from one of compulsion to one of choice. But this choice may be a purely nominal one. A residential society dominated by upper-caste members/families may protest against the inclusion of lower-caste residents. These residents may be excluded from social gatherings and events, particularly religious ones. Conservative upper-caste residents may consciously or unconsciously elect to avoid socializing with lower-caste residents. A variety of legal, social and communal pressures may drive lower-caste homeowners to choose residence in a society where they are subject to lesser alienation and scrutiny. Rental discrimination need not always be overt; even a seemingly benign listing like ‘Vegetarians only’ can ensure that only the traditionally vegetarian castes i.e. Bramhins are given accommodation. India Today reported that a real-estate site based in Bangalore asked for prospective tenants’ gotra, rashi, and nakshatram as a “subtle way of screening out undesirables.”12 The Human Rights Watch, in a report submitted to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, described the caste-system as “hidden apartheid”.13 In the same report, they drew special attention to the problem of segregated housing colonies for Dalits, lamenting the seeming complicity of the government in “maintaining the existing spatial segregation”, even “beyond rural environments”,14 also observing that many Dalits were systematically provided with no or poor state-services, a problem both caused and compounded by caste-based ghettoization. Evidently, desegregation is an important precursor for greater caste-inclusion and equality. However, in a 2005 judgement, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a cooperative society fighting to restrict its membership to Parsees, observing that “there should be a bond of common habits and common usage among the members, which should strengthen their neighborly feelings.”15 Indeed, in this situation, the exclusionary bye-laws of the society were protected by invoking the right of the minorities to safeguard their interests. This begs the question: should deghettoization be made a matter of compulsion? 12

Sanjay Hedge, Separate but equal ghettoes, INDIA TODAY (Nov. 12, 2013, 09:23am IST), https://www.indiatoday.in/opinion/story/muslims-hindu-colonies-ghettoisation-dalits-castes-religiondiscrimination-217151-2013-11-12. 13 India: ‘Hidden Apartheid’ of Discrimination Against Dalits, HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH (Feb. 13, 2007, 7:00pm EST), https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/02/13/india-hidden-apartheid-discrimination-against-dalits. 14 Id. 15 Zoroastrian Co-operative Housing Society Limited and Ors. v. District Registrar Co-operative Societies (Urban) and Ors., AIR 2005 SC 2306 (India). 5

It is also interesting to examine what the SC/ST Atrocities Act says about caste ghettoization. Perhaps to reconcile a respect for the personal preferences of lower-caste homeowners with a progressive desegregation policy, the Act only outlines the atrocities that an upper-caste person can commit against an SC/ST (wrongful occupation/dispossession of land, mischief to property, restriction of access to public spaces and facilities, etc.) 16, most of which are already offences under the IPC, simply aggrandized by the underlying castemotivation. The Act, hence, remedies individual injury while staying silent about community or group-based behavior.

16

The Scheduled Castes and The Scheduled Tribes (Prevention Of Atrocities) Act, 1989, No. 33, Acts of Parliament, 1989 (India). 6

2

CONCLUSION Much of modern-day ghettoization is unplanned. However, even this organic

ghettoization is a form of segregation. For divisions made on caste-based lines, ghettoization can lead to the systematic ousting of minority groups from society, the concentration of poverty in particular regions, lack of sustainable access to adequate infrastructural facilities due to geographic or economic considerations, and a general loss of socio-economic prosperity and mobility. Deghettoization is a two-pronged problem: preventing turfprotection by upper-castes, and promoting the interests of the minorities. The problem of how to go about desegregating, though, lies squarely in the legislative domain, and must be rectified through prohibiting otherizing covenants. As seen in its 2005 judgement, the courts can only decide if these covenants are constitutionally valid, not whether they are consonant with public interest per se.17 Johan Galtung wrote about segmentation, fragmentation, and marginalization as consonant processes that were manifestations of embedded cultural violence. 18 Ghettoization, whether enforced through legal or socio-cultural means, is a tool of repression that dissocializes minorities, enables discrimination and stereotyping, and undermines their collective identity.

17 18

Supra note 16. Johan Galtung, Cultural Violence, Volume 27 JOURNAL OF PEACE RESEARCH, 291, 293 (1990). 7

EXAMINING ‘ZOOTOPIA’: CASTE-BASED GHETTOIZATION IN MODERN INDIA SUBJECT: LAW AND LANGUAGE

SUBMITTED TO: DR. UMA MAHESHWARI CHIMIRALA SUBMITTED BY: NATASHA SINGH, 2019-5LLB-88 YEAR 1, SEMESTER 1

CONTENTS 1

Introduction.........................................................................................................................1

2

Legal Themes: Caste Ghettoization....................................................................................4

3

Conclusion..........................................................................................................................6

1

INTRODUCTION Zootopia released in 2016 to widespread critical acclaim. The title is a portmanteau of

the Latin root zoo-, meaning ‘living-being’ or ‘animal’, and the sociological concept ‘utopia’, which represents an ideal or perfect society. Likened to George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), the story centres on a futuristic society of anthropomorphic animals, set in an advanced time where animals have learnt to coexist peacefully. The protagonist of the story is a spunky rabbit, Judy, who dreams of becoming the first bunny police-officer. She is drawn into an investigation of violent crimes being perpetrated by the previously-civilised predators against prey. Like Animal Farm before it, Zootopia uses species/families of animals to represent the distinct classes in society. Predictably, the ‘lower’ classes of animals symbolise the traditionally marginalized communities, while the predators occupy positions of power, influence, and importance. Zootopia executes this concept while maintaining fidelity to the natural status quo: a carnivorous predator is outnumbered ten-to-one by its herbivorous prey. This means that the timorous grass-eaters comprise the bulk of the electorate in the fictional land where these mammals dwell, effectively turning the food chain on its head. Perhaps more importantly, Zootopia, like its literary predecessor, satirizes the broader political setting of the day. Orwell, who felt a strong distaste for what he felt was the ideologically bankrupt UK-USSR alliance, stated he wrote Animal Farm with a “full consciousness”1, intending “to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole.”2 Similarly, critics deconstructing Zootopia have commended the film’s “smart, funny and thought-provoking”3 message. Zootopia was reviewed by the American film-critic Peter Travers for Rolling Stone, the Indian journalist Reagan Gavin Rasquinha for The Times of India, and the British filmcritic John Nugent for Empire. Interestingly, all three different reviews analyzed Zootopia differently. The critics recognized that Zootopia has a hidden message; they were simply divided over what it was. Considering that the movie was an American production, many felt the central theme of fear, alienation and xenophobia was a thinly-veiled reference to the 11

George Orwell, Why I Write, GANGREL, Summer 1946. Id. 3 Neil Genzlinger, Review: In ‘Zootopia,’ an Intrepid Country Bunny Chases Her Dreams In The Big City, THE NEW YORK TIMES, March 23, 2016 at page 6, Section C. 2

1

politically charged climate of the divisive presidential-election. In his Rolling Stones review, Travers described Zootopia as a “subversive”4 movie that “put a lot on its animated plate”,5 interpreting its depiction of the treatment of meat-eating species as potential threats as an analogue to the US government’s notorious policy on racial-profiling. In the UK, where it was released under the alternative title Zootropolis, Empire magazine praised the movie for its rich detailing, acknowledging the uneasy onscreen predator-prey relationship as a “smart analogy for the debates on immigration that rage in our human world”6. While Rasquinha avoided explicitly politicizing the movie, he complimented it as an “intelligent”7 movie which avoided being “too moralistic”8 about weighty issues. Due to the wide scope of interpretation, and the marketing of Zootopia as a children’s movie, a majority of the reviews eschewed focusing solely on the socio-political issues the film touched upon, and instead lauded its core message of acceptance, rationality, and tolerance. When examined in a specifically Indian context, several points of interest crop up. The film experiments with a variety of themes that have legal and social significance. These include ghettoization, vertical occupational legacy, social pigeonholing, and institutionalized discrimination. Caste-like stratifications, particularly with reference to occupational heredity and endogamy, are strikingly ubiquitous. Japan, too, for example, had a highly inflexible system of social stratification (mibunsei) during the Edo period (1603-1868). Mibunsei was based on a Confucian conception of ‘moral purity’. Those who bore arms and protected others (samurais) were accorded the highest respect in society, followed by peasants and artisans, who produced goods and services. Last of all were the merchant-bankers, who dealt with wealth and money (typically viewed as corrupting influences). Parallel to the Indian Varnasystem, there were also those outside this system entirely. These outcast groups included Burakumin, who carried out the traditionally ‘tainted’ professions (undertaking, gravedigging, scavenging, etc.) The word Burakumin itself literally translates to “village people” or “hamlet people”, a testament to how severely they were physically segregated 4

Peter Travers, ‘Zootopia’ Movie Review, ROLLING STONE (Mar. 3, 2016, 2:22pm ET), https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-reviews/zootopia-92993. 5 Id. 6 John Nugent, Zootropolis Review, EMPIRE ONLINE (Mar. 18, 2016), https://www.empireonline.com/movies/reviews/zootropolis-review. 7 Reagan Gavin Rasquinha, Zootopia Movie Review, THE TIMES OF INDIA (May 9, 2016, 02.34pm IST), https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/english/movie-reviews/zootopia/moviereview/51238901.cms. 8 Id. 2

from mainstream society. The Burakumin scholar Nakagami Kenji analysed the experiences of the Burakumin relative to the other “marginalized outcastes”, noting that the routine exclusion of subaltern communities from the dominant-hegemonic socio-political processes systematically denied their beliefs, feelings, and experiences.9

9

Machiko Ishikawa, Nakagami Kenji’s ‘Writing Back to the Centre’ through the Subaltern Narrative: Reading the Hidden Outcast Voice in ‘Misaki’ and Karekinada, Volume 5, NEW VOICES, 1, 2-3 (2011). 3

1

LEGAL THEMES: CASTE GHETTOIZATION Judy, the protagonist, lives in the rural Bunnyburrow, an overpopulated village inhabited

exclusively by rabbits and hares. As the movie progresses, we see that the degree of segregation is extreme. Gerbils, hamsters, and other rodents dwell in Little Rodentia. Smaller animals prefer to live well away from the larger, more dangerous ones. Judy is desperate to escape the oppressive banality of her hometown to the relatively cosmopolitan capital Zootopia. The Oxford Dictionary defines a ghetto as “a part of a city, especially a slum area, occupied by a minority group or groups”, or alternatively as “an isolated group or area.” The definition, even in a non-sociological context, is suggestive of a level of segregation that forces certain members of society to live apart from the others. The first recorded use of the term was in the early 1700s, with reference to the infamous Venetian Jewish Ghetto. The word may have been derived from the Latin phrase Giudaicetum, which literally translates to ‘Jewish enclave’, or alternatively, from the Germanic-Italian word borghetto (the root of the English word borough), meaning ‘little town’.10 Despite the supposed European etymological origin of the word, the phenomenon of a ghetto, particularly a Dalit one, is oft-seen in Indian cities and villages. Fa Xian, the ChineseBuddhist traveler who wrote an account of early 5 th century India, observed that the Chandala caste, traditionally regarded as ‘impure’ or ‘evil by karma’, was made to live on the outskirts of the town or the village. 11 Centuries of deep-seated dogma, including the persistent belief that any form of contact, however minimal, with a Dalit would ‘pollute’ the upper-caste Hindus ensured that Dalits could only reside in small clusters of hamlets at a prescribed distance from the town temple, lake, and market. In other settlements with a sizeable Dalit population, the lower-castes were forced to use different wells, footpaths, and roads constructed exclusively for their use.

10

Camila Domonoske, Segregated From Its History, How 'Ghetto' Lost Its Meaning, NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO (Apr. 27, 2014, 12:46pm ET), https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/04/27/306829915/segregatedfrom-its-history-how-ghetto-lost-its-meaning. 11 RONALD MELLOR & AMANDA H. PODANY, THE WORLD IN ANCIENT TIMES: PRIMARY SOURCES AND REFERENCE VOLUME 76-77 (Oxford University Press 2005). 11

4

Many believe that the problem of ghettoization has since shifted from one of compulsion to one of choice. But this choice may be a purely nominal one. A residential society dominated by upper-caste members/families may protest against the inclusion of lower-caste residents. These residents may be excluded from social gatherings and events, particularly religious ones. Conservative upper-caste residents may consciously or unconsciously elect to avoid socializing with lower-caste residents. A variety of legal, social and communal pressures may drive lower-caste homeowners to choose residence in a society where they are subject to lesser alienation and scrutiny. Rental discrimination need not always be overt; even a seemingly benign listing like ‘Vegetarians only’ can ensure that only the traditionally vegetarian castes i.e. Bramhins are given accommodation. India Today reported that a real-estate site based in Bangalore asked for prospective tenants’ gotra, rashi, and nakshatram as a “subtle way of screening out undesirables.”12 The Human Rights Watch, in a report submitted to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, described the caste-system as “hidden apartheid”.13 In the same report, they drew special attention to the problem of segregated housing colonies for Dalits, lamenting the seeming complicity of the government in “maintaining the existing spatial segregation”, even “beyond rural environments”,14 also observing that many Dalits were systematically provided with no or poor state-services, a problem both caused and compounded by caste-based ghettoization. Evidently, desegregation is an important precursor for greater caste-inclusion and equality. However, in a 2005 judgement, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a cooperative society fighting to restrict its membership to Parsees, observing that “there should be a bond of common habits and common usage among the members, which should strengthen their neighborly feelings.”15 Indeed, in this situation, the exclusionary bye-laws of the society were protected by invoking the right of the minorities to safeguard their interests. This begs the question: should deghettoization be made a matter of compulsion? 12

Sanjay Hedge, Separate but equal ghettoes, INDIA TODAY (Nov. 12, 2013, 09:23am IST), https://www.indiatoday.in/opinion/story/muslims-hindu-colonies-ghettoisation-dalits-castes-religiondiscrimination-217151-2013-11-12. 13 India: ‘Hidden Apartheid’ of Discrimination Against Dalits, HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH (Feb. 13, 2007, 7:00pm EST), https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/02/13/india-hidden-apartheid-discrimination-against-dalits. 14 Id. 15 Zoroastrian Co-operative Housing Society Limited and Ors. v. District Registrar Co-operative Societies (Urban) and Ors., AIR 2005 SC 2306 (India). 5

It is also interesting to examine what the SC/ST Atrocities Act says about caste ghettoization. Perhaps to reconcile a respect for the personal preferences of lower-caste homeowners with a progressive desegregation policy, the Act only outlines the atrocities that an upper-caste person can commit against an SC/ST (wrongful occupation/dispossession of land, mischief to property, restriction of access to public spaces and facilities, etc.) 16, most of which are already offences under the IPC, simply aggrandized by the underlying castemotivation. The Act, hence, remedies individual injury while staying silent about community or group-based behavior.

16

The Scheduled Castes and The Scheduled Tribes (Prevention Of Atrocities) Act, 1989, No. 33, Acts of Parliament, 1989 (India). 6

2

CONCLUSION Much of modern-day ghettoization is unplanned. However, even this organic

ghettoization is a form of segregation. For divisions made on caste-based lines, ghettoization can lead to the systematic ousting of minority groups from society, the concentration of poverty in particular regions, lack of sustainable access to adequate infrastructural facilities due to geographic or economic considerations, and a general loss of socio-economic prosperity and mobility. Deghettoization is a two-pronged problem: preventing turfprotection by upper-castes, and promoting the interests of the minorities. The problem of how to go about desegregating, though, lies squarely in the legislative domain, and must be rectified through prohibiting otherizing covenants. As seen in its 2005 judgement, the courts can only decide if these covenants are constitutionally valid, not whether they are consonant with public interest per se.17 Johan Galtung wrote about segmentation, fragmentation, and marginalization as consonant processes that were manifestations of embedded cultural violence. 18 Ghettoization, whether enforced through legal or socio-cultural means, is a tool of repression that dissocializes minorities, enables discrimination and stereotyping, and undermines their collective identity.

17 18

Supra note 16. Johan Galtung, Cultural Violence, Volume 27 JOURNAL OF PEACE RESEARCH, 291, 293 (1990). 7

Related Documents

Project I - English I Movie Review

January 2021 1

Movie Review

January 2021 1

Movie Review Rubric

January 2021 1

I I I I I I

March 2021 0

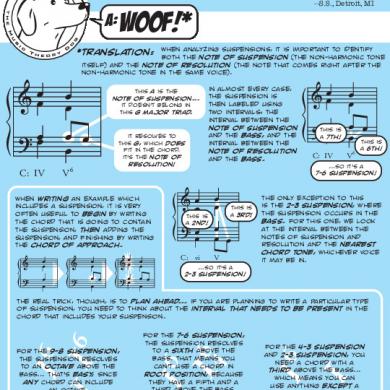

Woof!*: I I I I I I I

January 2021 1

Review Of Reservoir Engineering I

March 2021 0More Documents from "esther_lim_29"

Tipos De Articulaciones

February 2021 2

Project I - English I Movie Review

January 2021 1

Some Thoughts On Color

January 2021 1

Vertigo Tarot (book + Cards)

March 2021 0